Where I am:

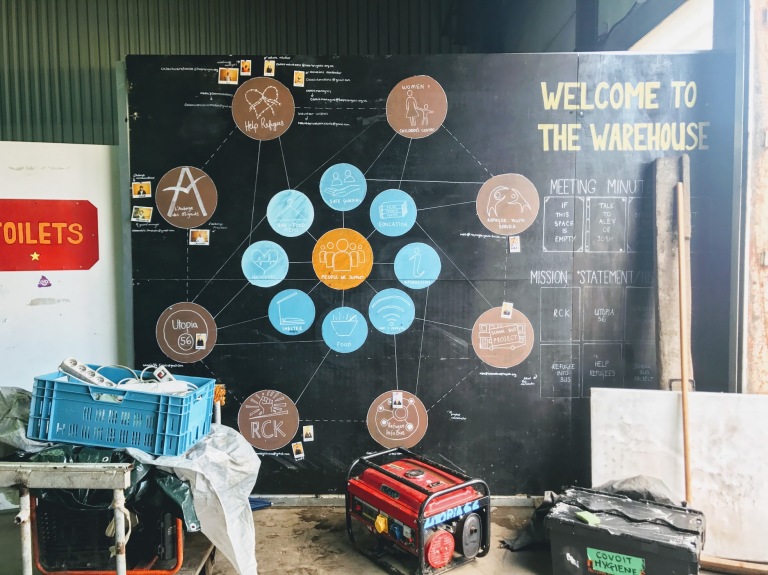

I cannot recall knowing where I would be on May 1st, 2018 as I had hardly a clue about where August in Kuala Lumpur would take me. Around this time last year, I was in recovery mode from submitting a thesis on nanoparticles. Currently, my arms are a bit sore from cutting 9 liters of onions with a group of French and British volunteers at the Refugee Calais Kitchen.

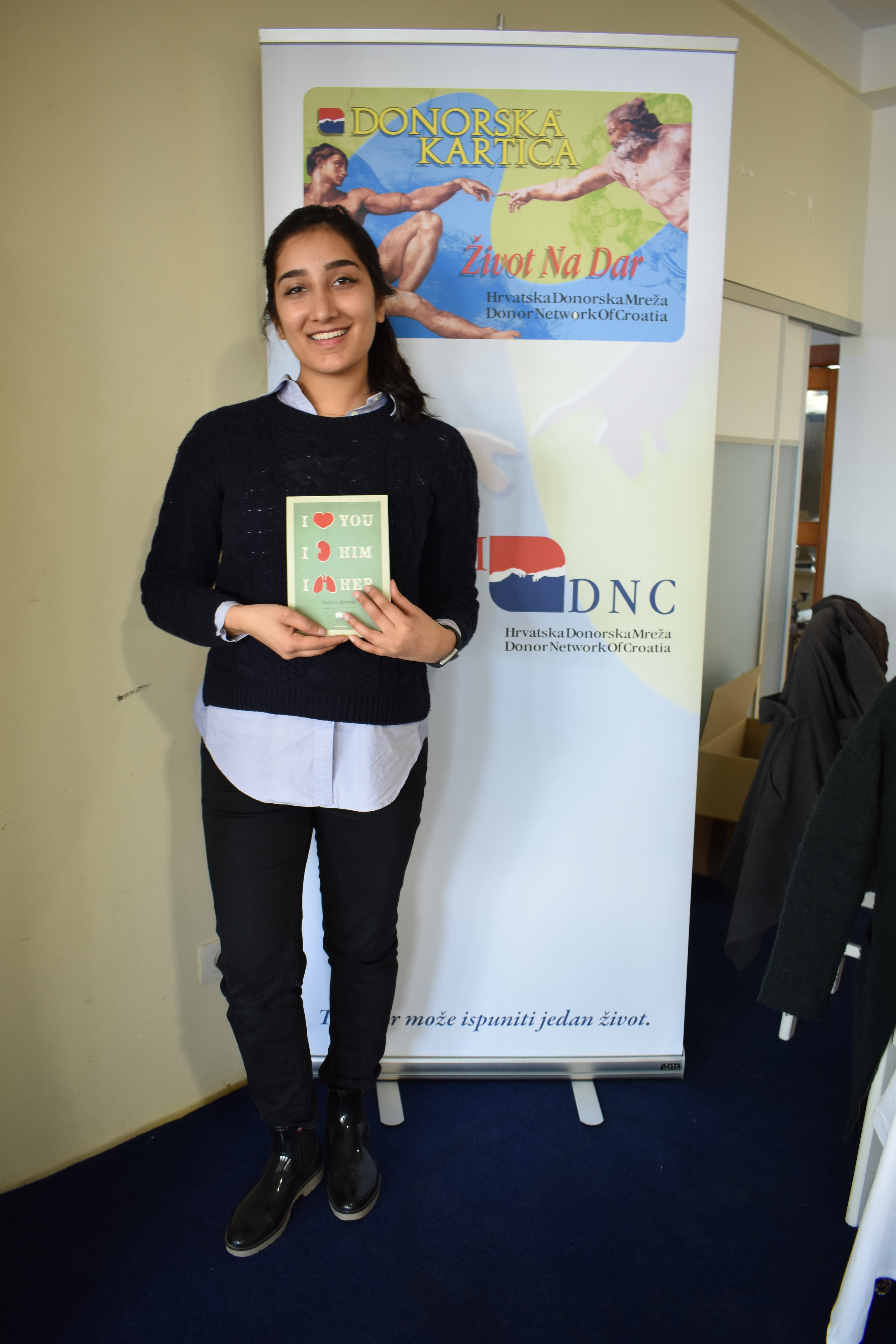

Here, I find myself in transition between two countries I hope to know better and to help with a crisis that defines our world today. Today also brings less joyous, more complicated events. My Croatian host mom said goodbye to her lovely mother, who fell ill on the day of my departure. She updated me today to let me know that she decided to donate their mother’s liver and kidneys, and how she found hope from the transplantation. I am thinking about what it means to honor a life today.

Where I was:

For organization, I’ll briefly explain what happened in the past three months as it’s a bit of a ramble later. I apologize again for my verbosity—there’s so much I want to share with you! I wrote to you at the end of my time in Lyon, France. I soon after left for Strasbourg for a month with a wonderful host family. I then went to Zagreb, Croatia where I lived with students. I then spent a few weeks along the coast, attending conferences and then living on a farm homestay in the religious old city during Easter. After Croatia, I returned to France: first to Paris and then to Calais. I am currently volunteering at the refugee camp in Calais. Here, I spend my days cooking and distributing food to refugees, while surprisingly learning quite a bit about some UK perspectives on organ donation from amazing, caring individuals. I hope to leave on May 6th for Birmingham, UK where I will pursue a work experience with a transplant surgeon. After the UK, I will observe the end of Ramadan in Morocco, before attending an international interfaith festival in Fez and then the annual Transplantation Society conference in Madrid. I hope my last month of my journey will be in London before returning to the States for the Watson conference.

A three-months summary:

In the European capital of Strasbourg, I walked kilometers a day, between meetings and bioethics lectures, between cups of coffee and trips to the Saturday market. I met with a medley of individuals, from NGO directors to cardiologists to youth activists, from interviewing the Head of the Bioethics division of the Conseil of Europe to a Muslim doctor working to encourage his community to donate. I found friends among university students, people 20 years my senior or 10 years my junior, including my host mom and her beautiful two children who created a home for me. The area of Alsace, where this German-French city is located, is the only region of France where the expectations of laicity are relaxed; for example, the public university supports a Catholic faculty. The reason for this exception is that within the past decades, Germany and France interchanged control over the city. Thus, the city still abides by some German law, including ones around the public practice of religion. Strasbourg serves as a legal interest further as it houses the European Union headquarters, which identifies consensus in the continent.

While I have not necessarily crossed borders, I find that European countries are not siloed, especially not their border cities like Strasbourg, Nice, or Calais. In Strasbourg, you could find a French, German, or even an “European” perspective. This fluidity brought me shortly to nearby borders for several reasons: the ease of travel and the osmosis of people. In France, I realized, while I may focus my research on the beliefs held by individuals within a certain country, it’s almost impossible to consider any opinion purely French or be unreceptive to whatever may be an un-French opinion. While being cognizant and immersive is my hope, my learning does not need to be framed around the country, but the people I meet.

However, I found this to be true to a lesser extent in Croatia. Landing in Zagreb in the beginning of March, I walked into a snowy landscape. Croatia was out of tourist season; there were very few people who were not white and even fewer who looked like me. The country is majorly Roman Catholic and incredibly homogenous, due to the war and ethnic cleansing in the area. Though I have preferred religiously diverse cities, I chose to go to Croatia because I thought I could learn about a different perspective: one that contrasts with Western Europe and offers insight into the unfamiliar.

Though some studies suggest Catholics in the U.S. are less likely to donate their organs, Croatia is one of the strongest, if not the best, in organ donation in the world. In the past ten years, during the post-war recovery, Croatia remarkably rose from the bottom of the list to the top, unlike its neighbors. I have wondered how much does religious diversity or homogeneity help with organ donation: does the presence of other opinions encourage us to ask of our own or does a consensus make it easier for us to know our own? In Croatia, at least, the answer is clearer, as Catholicism has a definitive organization with an ultimate leader. In their campaigns, the Ministry of Health of Croatia always uses quotations from Pope Francis and Pope John Paul II, who both publicly encouraged organ donation. The Ahmadiyya community of Zagreb, which also has a strong structure, was clear on organ donation, while the Baptist community was a bit vaguer.

Yet, I think another element, beyond religious permissibility or infrastructure, is critical to the success of organ donation, especially within more atheistic populations. At a Transplant Procurement Management course, held jointly by the Ministry and the Barcelona team, which trains country representatives from around the word, I had the privilege to meet different coordinators from the Balkans. We talked an incredible amount about trust. People need to trust in their healthcare systems, doctors, and governments to support organ donation. In the neighboring Bosnia, a lack of trust is intermixed with fear of organ trafficking. The people I met in Indonesia and some of ethic minorities in Malaysia did not trust their government, and often expressed negative outlooks on organ donation. Organ donation rates fell in Germany after a scandal where doctors prioritized richer patients was revealed.

Trust in others and in systems permeates the ethics of organ donation. In Croatia and France, consent is presumed, and everyone is a potential donor. While doctors are not obligated to respect the families wishes by French law, most medical professionals readily admit and argue that if the family is experiences emotional distress at donating organs, the procurement will not proceed. Croatian law however emphasizes family consent. This is done to preserve trust. However, do people not trust but then fear/respect the government in Singapore? In Singapore, procurement does proceed and has led to heart wrenching public disputes between the family and patients, often leading to pay-offs where the family receives five-years of discounted healthcare. Despite this, organ donation rates in Singapore remains near the world average.

Organ donation warrants conversation on trust but also on subsidiary questions. When it comes to question of consent, we can ask: do we respect the family or the donor’s wishes? When it comes to religion, we can ask: what does it mean to die and how can we respect the death process? For Hasidic Jews, brain death is contentious as death is defined when the heart stops beating. Some even argue that organ donation demands killing to save a life, and hold that brain death is but severe brain damage where a person is extraordinary differently abled but very much, still alive. We can also ask of the right to access. There is a global shortage of organs. Who deserves to get them? Should we give priority to people who have agreed to donate? Should we prioritize people with the same passport. In France and Croatia, likely because of the greater fluidity and migration, I have been perplexed by what is fair in allocating organs. To some respect, I can understand that citizens of a country should have priority in receiving. However, Croatia has an incredibly strong system of organ donation; it’s also a part of a seven-country alliance, Eurotransplant, which shares organs across borders if matches cannot be made within country. Catholic Croats—those with a Croatian passport—living in Bosnia can access the network. That means, effectively, that everyone on the right side of Mostar can easily receive a transplantation, while the Bosnian Muslims on the left side can maybe access 6% of Eurotransplant organs. While the Croatian Ministry is working to build systems in neighboring countries, the prospects are dim. I accept the rationality and feasibility of organ allocations, but I cannot help but feel disturbed by what seem to be moral allowances. My frustration recently stems from learning that U.S. patients with better health insurance can have higher probability of organ transplantation.

It also stems by my current mindset. In Calais, as I currently volunteer, I recall a conversation with a Strasbourg doctor who explained to me how migrants and refugees can access the organ donation list in the country if they have the money. However, the outcomes are pessimistic, as the transplantation process is taxing—either the refugee does not have stable medical care or social support. On the other hand, many refugees can be skeptical of any organ donation effort—one of the first medical checkpoints is to ensure the refugee is not suffering from infections induced by violent kidney harvesting. When organ trafficking is not involved, still skepticism exists as numerous Middle Eastern and North African countries, Morocco included, and many Muslim populations included, dispute the permissibility of the medical innovation. As migration continues, many new perspectives will be integrated into society, and I currently think Europe has much to gain from paying more attention to organ donation among minorities. Studies suggest that minorities have a tough time with organ donation, due to trust, such as the case of Blacks in the U.S. due to a history of medical betrayal, or a lack of communal understanding among diasporic communities. Neither France nor Croatia, to my understanding, supports research on organ donation outcomes among minorities (though I did meet with one organization in Zagreb who is open to the idea of starting such a program). I think, however, in increasingly diverse communities, it is critical to investigate any differences. We cannot help if we do not know where the help is needed.

While organ donation is life-saving—a beautiful gift and a tangible connection between people of widely different lives—it is a privilege of well-structured healthcare systems and individuals of means. I have learned immensely about it; yet, the complexity of how it is perceived has only become more nuanced. I have founder a deeper appreciation for ethics: how we choose to live and end our lives righteously. I don’t think I will ever get bored of learning about another and why they think, though how contrastingly or commonly they believe. After all, the monuments will stay for centuries, but people are fleeting, and I truly believe I am happiest deep into conversation.

Overall reflections:

I have realized the manners, approach, even the questions, and the people I have encountered in seeking an understanding of religious and cultural beliefs about organ donation have changed according to country, and then specifically, according to identity and geolocation. Many questions, however, remain constant especially when tied to my social location; I know much of my queries are due to a desire to understand myself: why did I hesitate about being an organ donor when I was 16? Why and how do I believe as a Muslim? I think I am learning as much as about religion and faith, as I am learning about organ donation; though, I feel that in Europe, religion is considered more suspiciously and privately; people seemingly take longer to open unless they are atheists. Even then, conversations are contrastingly Christian-centric. Among other questions I am considering is the popular existential one: what do I want to do with my life? Maybe the core of my identity is steadfast, but I imagine I have changed; I don’t sweat the small things as much, and I have fewer social fears or anxieties. I now strongly believe that upheavals or disappointments or other stress-inducing calamities happen for the best; we learn in discomfort and we know ourselves better. I have found a love for bioethics and a deeper appreciation for medicine and spirituality. And most surprisingly, I like chocolate ice cream now.

When I try to think back on my year thus far, I realize how long and short ago my time in Southeast Asia was. Somethings, like the feel of the soil, I cannot remember accurately, but a call to a friend or even the accent of Bahasa pulls me back. Someone mentioned to me that travelling was like time-travel, as it’s beyond liminal space or our own understanding of the time. I think she was right, and I still have not gotten over the surrealism of this year. I also have not gotten over what a gift and privilege a Watson fellowship is. I feel underserving of it—I don’t mean that in a self-deprecating way—I have benefitted immensely from an opportunity that is simply not available to so many people of the world. I think this feeling compels me to think of how I can honor this opportunity. It compels to think of how I can share my experience with others.

In my backpack, I carry three notebooks full of notes and quotations from interviews. I have a recorder with a few recordings—none in Europe due to an adaptation to people’s comfort levels—and a camera full of pictures of sights or things that define my memories. My blog is less active than I imagined, as I find myself busier than expected—choosing to not let opportunity pass me by—and allow myself a longer haul of reflection. My journal, however, preserves fleeting thoughts that I imagine I may no longer actively remember. I think one question that occupies much of my thoughts is what I will do with all that I have learned. Those I interview always ask for a future copy, while those I meet express interest. I feel an obligation to share the conversations with over 100 experts, from organ recipients to transplant coordinators to religious leaders and government officials, in the countries I have had the privilege of visiting. To share the quiet moments of unexpected conversation and the stories of the friends I have met. I feel an obligation to share it justly and comprehensively, but I want to take the next three months to figure out if and then in what medium, on what timeline, and in what way—and most importantly, what I hope to achieve from it. If I were to share more fulfillingly, I’d want others to learn of the amazing individuals and organizations upon which I have stumbled and how they think. Through their stories, I hope others could begin to deeply think about their own thoughts about organ donation and how they choose to practice their faith.

In the past three months, I sought answers to questions, learning more but knowing less. I found myself in a few unexpected cities and plans A through E out the window. I knew loneliness and love, stability and insecurity, and perhaps most, the brilliance of humanity. I have loved every day, though the sun may not have shined, and negativity wrapped its hands around my ankles. I have loved every day as I felt strongly as I always had something to be happy or grateful for—a friend, conversations, a bed, the gift of the fellowship, and life itself. Home is still where I am and whatever my memories hold, but I also feel at home in this world. I didn’t quite understand this, but I realized this opportunity is all I ever dreamed of: to find a sense of belonginess in the world and obligation to it. During the next three months, I hope to deeply reflect on the past year, while of course not letting opportunity to pass me by. I hope to continue to seek ways to remain uncomfortable and to take moments to enjoy sunsets. I cannot wait to meet the individuals of whatever tomorrow brings. inshAllah.

Thank you and much love as always.